AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION TRIBUNAL

Applications by Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited and Suncorp Group Limited [2024] ACompT 1

IN THE AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION TRIBUNAL

ACT 1 of 2023 | |

Re: | Applications by Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited and Suncorp Group Limited for review of Australian Competition and Consumer Commission Merger Authorisation Determination MA1000023 |

Applicants: | Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited and Suncorp Group Limited |

Intervenor: | Bendigo and Adelaide Bank Limited |

DETERMINATION

TRIBUNAL: | Justice Halley (Deputy President) Dr J Walker (Member) Ms D Eilert (Member) |

DATE: | 20 February 2024 |

WHERE MADE: | Sydney |

THE TRIBUNAL DETERMINES AND DIRECTS THAT:

1. The determination of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) dated 4 August 2023 be set aside pursuant to s 102(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA).

2. Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (ANZ) is granted authorisation pursuant to s 88(1) and s 102(1) of the CCA to acquire from Suncorp Group Limited (SGL) 100% of the issued share capital in SBGH Limited, either directly or via a related body corporate of ANZ, and certain real estate and intellectual and other property rights held by other SGL entities to facilitate the operation of Suncorp-Metway Limited, in accordance with a share sale and purchase agreement between ANZ and SGL executed on 18 July 2022.

3. Until further direction of the Tribunal, the reasons of the Tribunal in this proceeding dated today are not to be made available to or published to any person save for:

(a) the ACCC, its staff and any other person assisting the ACCC in relation to the proceeding including the ACCC’s legal advisers; and

(b) the parties’ legal advisers who, by reason of previous directions of the Tribunal, are permitted to have access to the confidential information of each of the parties to the proceeding.

4. Within 10 days of the date hereof, the parties are to file jointly:

(a) a copy of the Tribunal’s reasons that marks, by way of coloured shading, those parts of the reasons that a party or the ACCC seeks to have redacted on the grounds of commercial confidentiality or on the grounds that the information is protected information for the purposes of s 56 of the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority Act 1998 (APRA Act). Different coloured shading is to be used for each party, the ACCC and information that is protected information for the purposes of s 56 of the APRA Act; and

(b) short submissions addressing the basis for the claim of confidentiality on behalf of each party and the extent to which those confidentiality claims are agreed.

5. Nothing in these directions prevents the ACCC from consulting with the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) in respect of the reasons of the Tribunal.

THE TRIBUNAL:

1 The applicants, Australian and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (ANZ) and Suncorp Group Limited (SGL), seek a review by the Tribunal of a decision by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), on 4 August 2023, not to authorise an acquisition by ANZ of Suncorp-Metway Limited (Suncorp Bank) from SGL.

2 The ACCC declined to authorise the proposed acquisition because it was not satisfied that (a) the acquisition would not be likely to have the effect of substantially lessening competition in a national home loans market and in local or regional banking markets in Queensland for agribusiness customers and small to medium enterprises (SME), and (b) that the benefits to the public of the proposed acquisition would outweigh detriments to the public, from the proposed acquisition.

3 The applications by ANZ and SGL are opposed by Bendigo and Adelaide Bank Limited (Bendigo). Bendigo contends that the proposed acquisition of Suncorp Bank by ANZ would be likely to have the effect of substantially lessening competition in a national home loans market and in local or regional banking markets in Queensland for agribusiness customers. It contends that the acquisition of Suncorp Bank by ANZ would further consolidate ANZ’s market position and structural advantages as a major bank, without engaging in competition, to the substantial detriment of competition in the home loans and agribusiness markets.

4 In addition, the State of Queensland sought and was given leave to provide a submission for the sole purpose of clarifying information provided to the ACCC in connection with the making of its determination.

5 For the reasons that follow, the Tribunal is satisfied that the acquisition of Suncorp Bank by ANZ would not be likely to have the effect of substantially lessening competition in each of the national home loans market and local or regional Queensland markets for agribusiness customers and SME. Further, although strictly not necessary to determine given that finding, the Tribunal is also satisfied that the acquisition would be likely to result in a benefit to the public that would outweigh the detriment to the public that would be likely to result from the acquisition.

A.2. The commercial and economic context of the proposed acquisition

6 The Australian banking sector presently includes the four major banks: ANZ, Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA), National Australia Bank (NAB) and Westpac Banking Corporation (Westpac) (together, Major Banks), second-tier banks and other authorised deposit taking institutions (ADIs). The second-tier banks include banks at or around the size of Suncorp Bank, Macquarie Bank (Macquarie), ING Bank Australia (ING), Bendigo, Bank of Queensland and HSBC Bank Australia (HSBC). All of the Major Banks and second-tier banks are ADIs.

7 The Tribunal notes that beyond traditional non-bank lenders, since the Global Financial Crisis banking systems around the world have been facing threats of disruption from a range of digital players, particularly “BigTech” firms (large platform-based service providers such as Google, Apple and Amazon). As banking moves from a world of physical service delivery to one of digital service delivery, BigTech firms are expanding into financial services, particularly payment services.1

8 The threat posed by BigTech firms to the banking sector was summarised in the following terms in a [REDACTED] Board Paper from 2021:

[REDACTED]2

9 The Major Banks collectively account for 72% of reported banking system assets in Australia.3 The second-tier banks each have a share of banking system assets greater than 1% and collectively account for close to 14% of reported banking system assets, having increased their share of assets over the past decade. Other ADIs individually hold a share of banking system assets less than 0.7%, which includes 49 foreign bank branches, who primarily target niche areas and 57 credit unions and building societies, who operate under a mutual structure where customers are members and profits are reinvested back into the business.4

10 The share of the Major Banks, second-tier banks and other ADIs, as a proportion of banking system assets as at May 2023, are set out in the following table:5

11 Non-ADI lenders account for around 5% of total financial system assets in Australia.6 Non-ADI lenders include smaller financial technology providers which can be broadly described as “fintechs”.7

12 The Major Banks and the second-tier banks all provide retail and business banking services and have larger retail loan books than business loan books. Banks, however, focus on different customer segments and the relative size of their retail portfolio compared with their business portfolio will vary significantly by bank.8 For second-tier banks such as Bendigo, Bank of Queensland, ING, HSBC, Macquarie and Suncorp Bank, their retail lending (lending to households or individuals) represents between 78% and 89% of their total loan book. Suncorp Bank’s retail lending is 80% of its total loan book.9 It is generally the case that second-tier banks provide a higher proportion of retail lending relative to their business lending, than the Major Banks.

13 Smaller banks also have portfolios focused on particular business customer segments. For example, for [REDACTED], lending to SME customers accounts for between [REDACTED] of total business lending.10 The banks with the largest exposure to agribusiness lending as a proportion of their total business lending are [REDACTED].11

14 On 2 December 2022, ANZ lodged an application with the ACCC seeking authorisation under s 88(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA) for ANZ to acquire 100% of the shares in SGBH Limited from SGL pursuant to the terms of a share sale and purchase agreement between ANZ and SGL executed on 18 July 2022 (Proposed Acquisition). SGBH Limited is a non-operating holding company that owns 100% of the shares of Suncorp Bank, which together with its subsidiaries, owns and operates SGL’s banking business in Australia.

15 On 4 August 2023, the ACCC made a determination dismissing the application by ANZ for authorisation of the Proposed Acquisition.

16 The ACCC concluded with respect to competitive effects that:

Given the ACCC’s conclusions in relation to the markets for home loans, SME banking, and agribusiness banking, the ACCC is not satisfied in all the circumstances that the Proposed Acquisition is not likely to substantially lessen competition.12

17 The ACCC concluded with respect to public benefits and detriments that:

The ACCC is not satisfied, in all the circumstances, that the Proposed Acquisition would result, or be likely to result, in a benefit to the public that would outweigh the detriment to the public that would result, or be likely to result, from the Proposed Acquisition.13

18 The ACCC records in its determination that it commissioned and had regard to an expert report from Professor Nicolas de Roos and two expert reports from Mary Starks in reaching its conclusions. It also records that it had regard to submissions received from ANZ, SGL and interested parties, including:14

• ANZ’s application in support of the merger authorisation and related annexures including witness statements

• Expert reports provided by the merger parties and interested parties

• 27 submissions from interested parties in response to the ACCC’s initial consultation process including six confidential submissions

• over 20 submissions from interested parties following the ACCC’s statement of preliminary views

• ANZ’s response to submissions from interested parties,89 the ACCC’s statement of preliminary views, and Ms Starks’ reports, including witness statements and expert reports

• Suncorp Group’s response to submissions from interested parties, the ACCC’s statement of preliminary views, and Ms Starks’ reports, including witness statements and expert reports

• submissions from the merger parties

(Footnotes omitted.)

19 The ACCC provided the following summary of the submissions made by interested parties:

Overview of interested party submissions

3.26. Submissions to the ACCC from interested parties raise a variety of views on issues related to the Proposed Acquisition.

3.27. Several interested parties raised competition concerns regarding the Proposed Acquisition, noting:

• it would result in the removal of a significant second-tier competitor

• Suncorp Bank’s position in the supply to agribusiness markets

• there is inertia for customers switching between providers

• the low prospect of successful new entry and expansion in the industry

• increased consolidation of market share among major banks would make the relevant markets more susceptible to coordinated interactions.

3.28. In particular, CowBank and BMAgBiz submit that agribusiness customers have specialist needs and expressed concern that the Proposed Acquisition would reduce competition and availability of finance, particularly for bespoke agribusinesses with more complex needs. Judo Bank and Bank of Queensland submit that markets for supply to agribusiness and small to medium enterprise (SME) customers demonstrate state, regional and local characteristics.

3.29. BEN and Judo Bank submit that there is a realistic likelihood that Suncorp Bank, at least in part, could be acquired by another purchaser. BEN further submits that the counterfactual where Suncorp Bank is acquired by BEN is commercially realistic.

3.30. In addition to competition concerns, interested parties opposing authorisation generally raised concerns that the Proposed Acquisition would lead to public detriments and some questioned the extent to which synergies and benefits claimed by the merger parties will materialise if the Proposed Acquisition proceeds.

3.31. Particularly, several submissions expressed concerns that the Proposed Acquisition would reduce access to and quality of services due to branch closures and a focus away from Queensland and regional areas.

3.32. Similarly, the Consumers’ Federation of Australia, Clyde and Gail Andrews, and Property Rights Australia raise concerns that the Proposed Acquisition would impact on access to services for vulnerable customers including those in regional areas which may have poor internet access, elderly customers and those experiencing vulnerability.

3.33. Other interested parties, including an insurer, supported or expressed neutral views regarding authorisation. Rabobank expressed neutral views.

3.34. Interested parties supporting the Proposed Acquisition generally note that the major banks are subject to existing competitive pressure driving investment in technology, and that the Proposed Acquisition would enable Suncorp Group to be more focused and fill unmet client needs in the insurance industry.

3.35. The ACCC also received a large number of submissions from consumers. These submissions raise a number of concerns regarding the conduct of ANZ and Suncorp Bank and the Proposed Acquisition, including general concerns about competition and regulation in the Australian banking industry, such as applicable dispute resolution obligations, potential branch closures, attrition of Suncorp Bank employees and potential price increases. Several of these submissions also raise concerns about how ANZ and Suncorp Bank have handled individual disputes with their customers.

(Footnotes omitted.)

A.4. The application for review

20 On 25 August 2023, each of ANZ and SGL (collectively, the applicants) filed applications in the Tribunal pursuant to s 101 of the CCA for a review of the ACCC’s determination made on 4 August 2023. On 29 August 2023, the Tribunal made directions for the two applications to be determined together. There is no reason to distinguish between the applications and, in these reasons, the two applications will be referred to as the “application”. The Tribunal also notes that whilst each of the applicants filed separate concise statements of facts, issues and contentions (SOFIC) and submissions, in substance, the applicants advanced their case collectively. Each addressed different aspects of the application and adopted the submissions made by the other. The Tribunal, therefore, has considered it appropriate to address the submissions made by each of ANZ and SGL below, collectively, as the applicants’ submissions.

21 On 29 August 2023, the Tribunal also made a direction pursuant to s 109(2) of the CCA permitting Bendigo to intervene in this proceeding.

22 On 27 November 2023, the Tribunal made a direction that the State of Queensland file and serve the submissions annexed to an affidavit of Michael John Kimmins dated 6 October 2023, and on 15 December 2023, the Tribunal made a direction pursuant to s 102(10)(d) of the CCA formally requesting that the State of Queensland provide those submissions, for the sole purpose of clarifying information provided to the ACCC in connection with the making of its determination.

23 The application for authorisation filed by ANZ is a merger authorisation within the meaning of the CCA.

24 The Proposed Acquisition is subject to three conditions precedent (a) approval by the Federal Treasurer under the Financial Sector (Shareholdings) Act 1988 (Cth), (b) a final determination by the Tribunal to authorise the Proposed Acquisition or a declaration made by the Federal Court of Australia that the Proposed Acquisition would not contravene s 50 of the CCA, subject to there being no lodgements of a relevant application for review of the declaration or a notice of appeal, and (c) the State Financial Institutions and Metway Merger Act 1996 (Qld) (Metway Merger Act) being either repealed or amended such that it does not apply to any holding company of Suncorp Bank or ANZ or its related bodies corporate, with reference to certain agreed amendments and agreed commitments to the Queensland government set out in Schedule 17 of the Share Sale and Purchase Agreement or as otherwise agreed between the parties and the Queensland government.

25 A review by the Tribunal of authorisation determinations made by the ACCC is governed by the provisions of Pt IX of the CCA. As explained in the Tribunal’s decision in Applications by Telstra Corporation Limited and TPG Telecom Limited [2023] ACompT 1 (Telstra/TPG (No 1)) at [9] (O’Bryan J, Dr J Walker and Ms D Eilert), a review of a merger authorisation under Pt IX differs from a review of other authorisations in two material ways:

(a) first, a review of a merger authorisation is required to be completed by the Tribunal within a statutory time period (whereas a review of other authorisations is not subject to any time limit); and

(b) second, a review of a merger authorisation is not a re-hearing of the matter (whereas a review of other authorisations is a re-hearing of the matter) and, correspondingly, restrictions are imposed on the information, documents and evidence to which the Tribunal may have regard in a review of a merger authorisation (whereas no such restrictions are imposed in a review of other authorisations).

26 In the usual course, the statutory time period for the completion of a review of a merger authorisation is within 90 days. However, under s 102(1AD) of the CCA, the Tribunal may determine in writing that the matter cannot be dealt with properly within the initial period, either because of its complexity or because of other special circumstances, and that an extended period applies for the review, which consists of the initial period and a further specified period of not more than 90 days.

27 On 29 August 2023, the Tribunal made a determination in writing to that effect such that the period of the present review is 180 days, which ends on 20 February 2024.

28 With respect to the information, documents and evidence to which the Tribunal may have regard in this review, and in accordance with s 102(9) and s 102(10) of the CCA, the Tribunal has only had regard to (a) information that was referred to in the ACCC’s Reasons for Determination, (b) information furnished, documents produced or evidence given to the ACCC in connection with the making of its determination, (c) supplementary information provided to the Tribunal by the parties that did not exist at the time that the ACCC published its Reasons for Determination, and (d) information provided by the State of Queensland pursuant to the request from the Tribunal, for the sole purpose of clarifying information provided to the ACCC in connection with it making its determination.

29 The information, documents and evidence given to the ACCC in connection with the making of its determination was extensive. The ACCC received more than 50 submissions, 27 witness statements, 12 expert reports, and commissioned a further three expert reports. The ACCC also used its compulsory evidence gathering powers to require the applicants and other third parties to provide information and documents, which culminated in the ACCC receiving more than 200,000 documents. The ACCC conducted compulsory examinations on a number of individuals.15

30 The evidence given to the ACCC included a number of witness statements of executives of ANZ, SGL, Suncorp Bank, and Bendigo and expert reports prepared on behalf of those parties. The Tribunal has found the witness statements to be of assistance in understanding the commercial context in which the Proposed Acquisition arose and the options available to ANZ, SGL, Suncorp Bank, and Bendigo, if the Proposed Acquisition does not proceed. The witnesses who gave statements are summarised below.

31 SGL relied on statements from the following lay witnesses:

(a) Steve Johnston, the CEO of SGL, dated 25 November 2022, 17 May 2023 (two statements), and 13 July 2023;

(b) Clive van Horen, CEO of Suncorp Bank, dated 25 November 2022, 17 May 2023, and 14 July 2023; and

(c) Adam Bennett, CIO of SGL, dated 16 May 2023.

32 ANZ relied on statements from the following lay witnesses:

(a) Adrian Went, the Group Treasurer of ANZ, dated 28 November 2022 and 17 May 2023;

(b) Shayne Elliott, the CEO of ANZ, dated 30 November 2022, 17 May 2023, and 30 June 2023;

(c) Douglas John Campbell, the General Manager, Home Loans Australia, in the Australia Retail Division at ANZ, dated 30 November 2022 and 17 May 2023;

(d) Isaac James Christian Rankin, the Managing Director of Commercial and Private Banking at ANZ, dated 30 November 2022;

(e) Yiken Yang, General Manager, Deposits, ANZ, dated 30 November 2022 and 17 May 2023;

(f) Mark Bennett, Head of Agribusiness, Australia Commercial Division ANZ, dated 1 December 2022, 17 May 2023, and 7 July 2023;

(g) Guy Samuel Mendelson, Managing Director, Business Owners Portfolio, Australia Commercial Division ANZ, dated 1 December 2022;

(h) Peter Dalton, Managing Director Designer and Delivery ANZx, dated 13 December 2022;

(i) Louise Claire Higgins, Managing Director, Suncorp Integration ANZ, dated 17 May 2023 and 17 July 2023; and

(j) James Anthony Lane, State Manager of Business Banking, Queensland, Australia Commercial Division ANZ, dated 17 July 2023.

33 Bendigo relied on a witness statement made by Cameron Telford Stewart, Head of Mergers and Acquisitions at Bendigo, dated 3 March 2023.

34 In the course of its assessment of the application for authorisation, the ACCC also examined a number of those witnesses and other executives of the parties pursuant to its powers under s 155 of the CCA. The persons from ANZ examined by the ACCC were Mr Elliott, Mr Campbell, and Mr Yang. The persons from Suncorp Bank examined were Dr van Horen, Mr Johnston (examined twice), and Dean Cleland, Executive General Manager, Business Banking. The persons from Bendigo examined were Marnie Baker, CEO and Managing Director of Bendigo, (examined twice) and Ryan Brosnahan, Bendigo’s Chief Transformation Officer.

35 SGL relied on the following expert reports:

(a) a report prepared by Dr David Howell, dated 15 May 2023, addressing the likely issuer credit rating for a merged Bendigo/Suncorp Bank; and

(b) reports prepared by Mozammel Ali, dated 17 May 2023 and 23 July 2023, addressing the funding costs and challenges of the Proposed Acquisition, the second report responded to reports prepared by Ms Starks that address advanced internal ratings-based accreditation issues arising out of the Proposed Acquisition.

36 ANZ relied on the following expert reports:

(a) reports prepared by Dr Jeffery Carmichael AO, dated 25 November 2022 and 13 May 2023, addressing the prudential public benefits and detriments arising out of the Proposed Acquisition;

(b) reports prepared by Dr Phillip Williams AM, dated 1 December 2022 and 19 May 2023, addressing the likely competitive effects of the Proposed Acquisition in relation to the supply of banking products in Australia, identification of the relevant product and geographic dimensions of the market or markets for commercial banking products, and whether the Proposed Acquisition is likely to substantially lessen competition in relation to the relevant market or markets; and

(c) reports prepared by Patrick Smith, dated 1 December 2022, 17 May 2023, and 17 July 2023, addressing whether the net cost savings described in the workbook titled ‘Synergies and one-off costs’ would be a public benefit of the Proposed Acquisition and whether the impacts of the funding costs identified in the witness statement of Mr Went would be considered a public benefit.

37 Bendigo relied on expert reports prepared by Professor Stephen King, dated 3 March 2023 and 28 June 2023, addressing whether the Proposed Acquisition would have the effect of substantially lessening competition in any market in Australia and whether public benefits would outweigh detriments as a result of the Proposed Acquisition.

38 The ACCC relied on the following expert reports:

(a) a report prepared by Professor Nicolas de Roos, dated 5 April 2023, addressing the concept of “coordinated effects” as it applies to the competition assessment of mergers and acquisitions in general. The report further sets out a high-level framework for assessing any change in the likelihood, extent, or severity and sustainability of coordinated effects arising out of the Proposed Acquisition compared with a counterfactual in which the Proposed Acquisition did not proceed;

(b) a report prepared by Mary Starks, dated 16 June 2023, in response to the expert reports of Dr Williams, and Dr Carmichael. The report also addresses the appropriate markets or areas of competitive overlap for analysing the competitive effects of the Proposed Acquisition and whether the Proposed Acquisition would have the effect of substantially lessening competition in the relevant areas of competitive overlap; and

(c) a supplementary expert report prepared by Ms Starks, dated 7 July 2023, addressing whether any of her conclusions in her first report are altered considering the additional information provided to her listed at Annexure A of the supplementary report.

39 In accordance with Direction 13 of the directions made on 29 August 2023, as varied by Direction 11 of the directions made on 20 October 2023, the parties have prepared and filed a joint document identifying all findings on factual matters set out in the ACCC’s Reasons for Determination that are not contested by the parties on this review (Agreed Factual Findings).

40 The Tribunal has adopted the Agreed Factual Findings for the purposes of making this determination.

41 The Tribunal has also received and had regard to (a) the SOFICs filed on behalf of each of the parties to this proceeding, (b) written submissions filed on behalf of each of the parties in advance of the hearing, and (c) oral submissions advanced on behalf of each of the parties during the hearing, together with a number of aide memoires and further written submissions provided to the Tribunal during the hearing.

B. STATUTORY FRAMEWORK FOR THE TRIBUNAL’S REVIEW

42 The grant of authorisations by the ACCC under Pt VII of the CCA and the Tribunal’s review of determinations by the ACCC in respect of authorisation applications, was amended significantly by the Competition and Consumer Amendment (Competition Policy Review) Act 2017 (Cth) (2017 Amendment Act): see Telstra/TPG (No 1); Applications by Telstra Corporation Limited and TPG Telecom Limited (No 2) [2023] ACompT 2 (Telstra/TPG (No 2)); see also the Explanatory Memorandum to the enacting bill, the Competition and Consumer Amendment (Competition Policy Review) Bill 2017 (2017 Explanatory Memorandum).

43 The amendments largely implemented the recommendations from the Competition Policy Review chaired by Professor Ian Harper (Harper Review). Consistently with the Harper Review’s two principal recommendations in respect of authorisations, notifications and class exemptions, the 2017 Amendment Act purported to simplify the authorisation regime such that (a) only a single authorisation application was required for a single business arrangement or transaction, and (b) the ACCC was newly empowered to grant authorisation on the basis that the conduct would not be likely to substantially lessen competition.

44 The effect and purpose of the statutory provisions and principles relevant to an authorisation application were largely not in dispute between the parties.

45 The following consideration of the statutory framework and principles governing the Tribunal’s review in this matter was determined in accordance with the opinion of the presidential member presiding: s 42(1) of the CCA.

46 Section 88 of the CCA empowers the ACCC to grant authorisations in respect of conduct that would or might otherwise contravene the provisions prohibiting restrictive trade practices under Pt IV of the CCA and is relevantly expressed in the following terms:

88 Commission may grant authorisations

Granting an authorisation

(1) Subject to this Part, the Commission may, on an application by a person, grant an authorisation to a person to engage in conduct, specified in the authorisation, to which one or more provisions of Part IV specified in the authorisation would or might apply.

Note: For an extended meaning of engaging in conduct, see subsection 4(2).

47 While the authorisation remains in force, the provisions in Pt IV of the CCA will not apply in respect of the conduct that is the subject of the authorisation to the extent it is engaged in by the applicant, any other person named or referred to in the application as a person who is engaged in, or who is proposed to be engaged in, the conduct and any other particular persons or classes of persons, as specified in the authorisation, who become engaged in the conduct: s 88(2) of the CCA.

48 In respect of an authorisation application, the ACCC shall make a determination in writing either granting such authorisation as it considers appropriate or dismissing the application: s 90(1) of the CCA.

49 By s 90(7) of the CCA, the statutory preconditions to the determination of an authorisation application are expressed as follows:

90 Determination of applications of authorisations

…

(7) The Commission must not make a determination granting an authorisation under section 88 in relation to conduct unless:

(a) the Commission is satisfied in all the circumstances that the conduct would not have the effect, or would not be likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition; or

(b) the Commission is satisfied in all the circumstances that:

(i) the conduct would result, or be likely to result, in a benefit to the public; and

(ii) the benefit would outweigh the detriment to the public that would result, or be likely to result, from the conduct; or

50 An “authorisation” is defined in s 4 of the CCA to mean an authorisation under Div 1 of Pt VII granted by the ACCC or by the Tribunal on a review of the ACCC’s determination.

51 A “merger authorisation” is defined in s 4 of the CCA in the following terms:

merger authorisation means an authorisation that:

(a) is an authorisation for a person to engage in conduct to which section 50 or 50A would or might apply; but

(b) is not an authorisation for a person to engage in conduct to which any provision of Part IV other than section 50 or 50A would or might apply.

52 The effect of assigning a specific definition to “merger authorisation” is to limit such authorisations to conduct to which only s 50 or s 50A of the CCA would or might apply.

B.3. The review of the ACCC’s determination

53 A person dissatisfied with a determination by the ACCC under Div 1 of Pt VII of the CCA, in relation to an application for an authorisation may apply to the Tribunal for a review of the determination: s 101(1)(a) of the CCA. On a review of the ACCC’s determination in relation to an application for authorisation, the Tribunal may make a determination affirming, setting aside or varying the ACCC’s determination and, for the purposes of the review, may perform all the functions and exercise all the powers of the ACCC: s 102(1)(a) of the CCA. A determination by the Tribunal pursuant to s 102(1) is taken to be a determination of the ACCC: s 102(2) of the CCA.

54 The Tribunal’s task on review is to “make its own findings of fact and reach its own decision as to whether authorisation should be granted or not, and if so, any conditions to which it is to be subject”: Application by Medicines Australia Inc [2007] ACompT 4; (2007) ATPR 42-164 (Medicines Australia) at [135] (French J, Mr GF Latta and Prof C Walsh).

55 The Tribunal’s task in respect of a merger authorisation application does not, however, entail “full merits review” or a “rehearing” because of the time and commercial sensitivities specific to such transactions: 2017 Explanatory Memorandum at [15.49]; see also Telstra/TPG (No 1) at [50]; Telstra/TPG (No 2) at [107]. This rationale is reflected in certain of the requirements for merger authorisations, brought into effect by the 2017 Amendment Act, including that (a) the Tribunal’s review of the ACCC determination must be completed within 90 days and may only be extended in certain circumstances: s 102(1AC) of the CCA, and (b) the Tribunal, in conducting its review, may only have regard to the material that is enumerated in s 102(10) of the CCA. The limitations on the information that the Tribunal may have regard to, in conducting its review, is intended to ensure that applicants to a merger authorisation “do not delay production” of relevant material to the Tribunal. This facilitates, in turn, the Tribunal in conducting its review “expeditiously”: 2017 Explanatory Memorandum at [9.80].

56 The Tribunal’s function is not to consider the correctness of the ACCC’s determination or whether it could have been better formulated: Medicines Australia at [138]; Application by Flexigroup Ltd (No 2) [2020] ACompT 2 at [135] (O’Bryan J, Dr J Walker and Ms D Eilert). The published reasons for the ACCC’s determination can, however, provide a “convenient reference point” for defining the matters in dispute: Telstra/TPG (No 2) at [108]; Re Herald & Weekly Times Ltd (on Behalf of the Media Council of Australia) (1978) 17 ALR 281 at 296 (Deane J, Mr J Shipton and Mr J Walker). Further, to the extent that the parties agree with factual findings made by the ACCC in the course of its determination, the Tribunal, ordinarily, need not examine those facts in detail: Telstra/TPG (No 2) at [108].

B.4. Statutory preconditions to authorisation

57 Section 90(7) of the CCA enumerates two tests for authorisation under s 90(7)(a) and s 90(7)(b). The tests for authorisation are expressed in the alternative, and, accordingly, the Tribunal need only be satisfied that the applicant has discharged its onus in respect one of the authorisation tests.

58 No standard of proof applicable in a civil litigation context, such as the balance of probabilities, applies to decisions bearing an administrative character, as in this case: Telstra/TPG (No 2) at [99] and the authorities cited therein. Hence, the only relevant precondition to granting authorisation is the existence of the Tribunal’s satisfaction of one of the conditions under s 90(7)(a) or s 90(7)(b). Put another way, the ACCC or the Tribunal on review must reach an “affirmative belief” as to one of the matters under s 90(7)(a) or s 90(7)(b): Telstra/TPG (No 2) at [99]. This requisite state of satisfaction is to be formed in good faith, reasonably and upon a correct understanding of the law: Wei v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2015) 257 CLR 22; [2015] HCA 51 at [33] (Gageler J, as his Honour then was and Keane J); O’Connor v Construction, Forestry, Mining, Maritime and Energy Union [2023] FCAFC 151 at [34] (Rangiah, Wheelahan and Raper JJ).

59 Both tests for authorisation require the ACCC or the Tribunal on review to compare a future with and without the conduct that is the subject of the authorisation application. In this regard, the tests for authorisation direct primary focus to the effects of the conduct for which authorisation is sought rather than the effects of conduct that is coincident with but not causally related to the conduct the subject of the authorisation application: Telstra/TPG (No 2) at [145]-[147]. For example, in respect of the test under s 90(7)(b), public benefits that are the result of other coincident conduct that is not the subject of the authorisation application may not be taken into account.

B.5. Section 90(7)(a) – the competition test

60 The first test for authorisation requires the ACCC or the Tribunal on review to be satisfied that the conduct would not have the effect, or would not be likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition: s 90(7)(a).

61 The application of the test under s 90(7)(a) ultimately requires the relevant decision maker to engage in the following stages of analysis:

(a) identification of the relevant markets, being the “field of actual and potential transactions between buyers and sellers amongst whom there can be strong substitution, at least in the long run, if given a sufficient price incentive”: Re Queensland Co-Operative Milling Association Ltd; Re Defiance Holdings Ltd (1976) 8 ALR 481 (QCMA) at 513 (Woodward J, JAF Shipton Esq and Prof MD Brunt); and

(b) a comparison between the nature and extent of competition in any market potentially affected by the proposed conduct in a future where the proposed conduct occurs and in a future without the proposed conduct: Telstra/TPG (No 2) at [117]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pacific National Pty Ltd (2020) 277 FCR 49; [2020] FCAFC 77 (Pacific National) at [103] (Middleton and O’Bryan JJ) and the authorities cited therein.

62 Substitutability is the essential concept for market definition. It is perhaps best explained by asking would there be a significant switch in demand or supply in response to a relatively small price increase (all other competitive variables being unchanged).16 In practice, this is reflected in the test known as the hypothetical monopolist, small but significant and non-transitory increase in price (SSNIP) test. It asks whether a small but significant non-transitory increase in price by a hypothetical monopolist would be defeated by demand side substitution (consumers switching to other products) and/or supply side substitution (other firms commencing to supply the product quickly and without significant investment).

63 Further, in addressing market definition it is necessary to distinguish between substitution in supply and new entry. Substitution in supply occurs when a firm is able to make a switch in production that is relatively rapid, using existing assets and without incurring significant expenditure. New entry is likely to take much longer and require significant expenditure on the acquisition of new assets. The likelihood of entry or expansion is taken into account in the second stage of the analysis.

64 The test under s 90(7)(a) is not applicable to authorisations in respect of cartel conduct (Div 1 of Pt IV), secondary boycotts (s 45D to s 45DB), contracts etc. affecting the supply or acquisition of goods or services (s 45E to s 45EA) and resale price maintenance (s 48): s 90(8) of the CCA. The purpose of this limitation was explained in the 2017 Explanatory Memorandum at [9.44]:

This avoids a mismatch between the basis on which the conduct is prohibited, which does not look to whether the purpose, effect or likely effect of the conduct is a substantial lessening of competition, and the basis on which authorisation for that conduct may be granted.

65 Section 90(7)(a) is framed in similar language to s 45, s 46, s 47 and s 50 under Pt IV of the CCA, except for the following key differences.

66 First, s 90(7)(a) is expressed as a negative proposition. Therefore, contrary to the application of the similarly framed provisions in Pt IV of the CCA, s 90(7)(a) requires the Tribunal to be satisfied that the conduct would not have the effect, or would not be likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition. It does not necessarily follow that if the Tribunal is not satisfied that the conduct would have the effect, or would be likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition that the Tribunal must be satisfied that the conduct would not have the effect, or likely effect, of substantially lessening competition. In some cases, the Tribunal may be satisfied that it can make a negative finding that it was not satisfied the conduct would be likely to substantially lessen competition but might have insufficient evidence to make a positive finding that it was satisfied the conduct would not be likely to substantially lessen competition.

67 Second, proof of contravention of similarly framed provisions in Pt IV of the CCA requires proof on the balance of probabilities. The evidentiary burden of proof applicable in civil litigation, is not applicable to an administrative decision of the ACCC or the Tribunal. The Tribunal’s task in respect of s 90(7)(a) is to reach a state of satisfaction or an “affirmative belief” that the conduct the subject of the authorisation application would not have the effect, or would not be likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition.

68 Notwithstanding these differences, the principles developed in respect of the meaning of the “likely effect of substantially lessening competition” as it appears in the language of s 45, s 46, s 47 and s 50 of the CCA, are directly instructive to the application of s 90(7)(a) of the CCA. The meaning of the “likely effect of substantially lessening competition” has been canvassed in a large body of case law and was most recently considered by the Full Court of the Federal Court in Pacific National and the Tribunal in Telstra/TPG (No 2).

69 In Telstra/TPG (No 2), the Tribunal summarised the meaning of “competition” at [112] to [114]. The Tribunal relevantly stated at [114], by reference to O’Bryan J’s decision in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v BlueScope Steel Limited (No 5) [2022] FCA 1475 at [124]-[127], that:

[C]ompetition is best described by reference to its aim, mechanism and effect:

(a) The basic aim of business competition is to win sales – competitors strive to replace each other in the supply of products (whether goods or services) sought by customers.

(b) The key mechanism of competition is through substitution – to supply products to customers in place of another competitor’s supply. Substitution occurs on the demand side, whereby customers substitute one product or source of supply for another, and on the supply side, whereby suppliers adjust their production mix to substitute one product for another or one area of supply for another. Competitors strive to bring about substitution in a number of ways: through lowering their costs of production to enable them to profitably lower their prices; through improving the quality of their product and thereby increasing the value of the product to customers; and through inventing new products to meet the needs and wants of customers in new or better ways.

(c) As to effect, competition enhances the welfare of Australians by creating incentives and pressure for suppliers to reduce their costs of production and their prices (which, in the language of economics, is referred to as an improvement in productive efficiency), to commit resources to the production of goods and services most wanted by customers and to improve the quality of those products (which, in the language of economics, is referred to as an improvement in allocative efficiency) and to invest in innovation with the object of inventing new products to meet the needs and wants of customers (which, in the language of economics, is referred to as an improvement in dynamic efficiency).

70 Section 4G of the CCA provides further colour to the concept of lessening competition, provides that:

For the purposes of this Act, references to the lessening of competition shall be read as including references to preventing or hindering competition.

71 As to the meaning of “substantially”, Middleton and O’Bryan JJ stated in Pacific National at [104] that:

[T]he word does not connote a large or weighty lessening of competition, but one that is “real or of substance” and thereby meaningful and relevant to the competitive process.

(Emphasis added. Citations omitted.)

72 Critically, the meaning of “likely”, in the context of its application to an assessment of a substantial lessening of competition, has been the subject of significant scrutiny, judicially and before the Tribunal.

73 In Pacific National at [246] (Middleton and O’Bryan JJ), their Honours adopted the approach of French J in Australian Gas Light Co v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (No 3) (2003) 137 FCR 317; [2003] FCA 1525 at [348] and stated that “likely” means a “real commercial likelihood”. The Full Court stated at [246] that the determination of whether an acquisition or merger is likely to have the effect of substantially lessening competition requires the application of the following approach:

(a) the application of s 50 requires a single evaluative judgment;

(b) it is a distraction (and, we would add, wrong) to ask what standards of proof apply to the primary facts which will involve predictions about the future;

(c) however, the degree of likelihood of any particular future fact existing or arising will be relevant to the assessment of the likely effect on competition of the acquisition.

(References to primary judgment omitted.)

74 This approach was recently affirmed by the Tribunal in Telstra/TPG (No 2) at [117].

B.6. Section 90(7)(b) – the net public benefits test

75 The second test for authorisation requires the ACCC or the Tribunal on review to be satisfied that the conduct would result, or be likely to result, in a benefit to the public and the benefit would outweigh the detriment to the public that would result, or be likely to result, from the conduct: s 90(7)(b). The form of this second test is consistent with tests previously contained in s 90: 2017 Explanatory Memorandum at [9.41]; Telstra/TPG (No 2) at [120]. The principles developed in respect of previous iterations of s 90(7)(b), therefore, are directly applicable to the present iteration of the test. The relevant principles are summarised as follows.

76 The relevant “public” to which the test is directed, is the Australian public: QCMA at 507-8; Medicines Australia at [107].

77 A “benefit to the public” has a wide import and will include “anything of value to the community generally, any contribution to the aims pursued by the society including as one of its principal elements (in the context of trade practices legislation) the achievement of the economic goals of efficiency and progress”: QCMA at 507-508; Telstra/TPG (No 2) at [121]. A “benefit to the public” can take into account both group interests and individual interests, to the extent that such individual interests are, in accordance with general societal views, worthy of inclusion and measurement: Re Qantas Airways Ltd [2004] ACompT 9 (Qantas Airways) at [187] (Goldberg J, Mr GF Latta and Prof DK Round). In this regard, cost savings or productive efficiency gains achieved by a private firm can constitute a “benefit to the public” in circumstances where it ultimately leads to “public” outcomes including a reduction in prices to final consumers or dividends to a range of shareholders. The weight to be given to such costs savings, however, depends on the extent to which they are passed through to consumers: Qantas Airways at [189]-[190].

78 A “detriment to the public” can include “any impairment to the community generally, any harm or damage to the aims pursued by the society including as one of its principal elements the achievement of the goal of economic efficiency”: Re 7-Eleven Stores Pty Ltd (1994) 16 ATPR 41-357 at 42,683; Medicines Australia at [108]. In many cases, the most important potential detriments will flow from the anti-competitive effect, which will result, or is likely to result, from the conduct the subject of the authorisation application: Medicines Australia at [108]. It may be the case that a purported benefit when “viewed in terms of its contribution to a socially useful competitive process” is in fact, to be judged as a detriment to the public: QCMA at 510.

79 The test under s 90(7)(b) requires the ACCC or the Tribunal on review to undertake a balancing exercise in order to determine whether benefits to the public ultimately outweigh detriments to the public: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Competition Tribunal [2017] FCAFC 150 (ACCC v ACT) at [7] (Besanko, Perram and Robertson JJ); QCMA at 506. Such a balancing exercise will involve what has been described as an “instinctive synthesis”, not least because many of the purported benefits and detriment will be “incommensurable and possibly unmeasurable”: ACCC v ACT at [7].

80 The weight to be given to a particular “benefit” requires an assessment of its nature, characterisation and the identity of the beneficiaries to it: Qantas Airways at [188]. This includes discerning “who takes advantage [of the benefit to the public] and the time period over which the benefits are received”: Qantas Airways at [189]; Telstra/TPG (No 2) at [122].

81 An applicant for authorisation is required to show that there is a factual basis for concluding that the purported benefits are likely to result, rather than to quantify in precise terms, the benefits: Qantas Airways at [201]; Telstra/TPG (No 2) at [125]. Relevantly, in Telstra/TPG (No 2), the Tribunal adopted and provided the following summary of further principles governing benefit analysis, which were set out in Qantas Airways at [203]-[209]:

(a) an accurate, objective quantification of public benefits is difficult, in part because benefits have to be estimated for some period in the future and so their magnitude becomes a matter not only of empirical estimation based on assumptions but also one of statistical likelihood;

(b) the nature of public benefits should be defined with some precision, a degree of precision which lies somewhere between quantification in numerical terms at one end of the spectrum and general statements about possible or likely benefits at the other end of the spectrum;

(c) any estimates involved in benefit analysis should be robust and commercially realistic, in the sense of being both significant and tangible;

(d) appropriate weighting will be given to future benefits not achievable in any other less anti‑competitive way, and so the options for achieving the claimed benefits should be explored and presented;

(e) the Tribunal is not assisted by fanciful and speculative modelling of benefits where the underlying assumptions are not clearly spelled out, where the estimates have not been subject to rigorous sensitivity analysis, and where the estimating process is not wholly transparent;

(f) while detailed quantification of benefits is the best option, quantification is not required by the CCA and benefits should be quantified only to the extent that the exercise enlightens the Tribunal more than the alternative of qualitative explanation; and

(g) where benefits cannot be quantified in monetary terms, they can still be claimed in qualitative terms.

82 The power conferred on the ACCC or the Tribunal on review to authorise conduct is discretionary. The statutory criteria under s 90(7) are only necessary conditions and, therefore, satisfaction of the criteria does not oblige the ACCC or the Tribunal on review to grant authorisation: Telstra/TPG (No 2) at [127]; Medicines Australia at [106]. Given the large variety of circumstances to which the discretion may be applied, it is not necessary nor desirable to define its outer limits, other than to say that it is not narrowly confined and will be informed by the objectives of the CCA: Medicines Australia at [126]; Water Conservation and Irrigation Commission (NSW) v Browning (1947) 74 CLR 492 at 505; Oshlack v Richmond River Council (1998) 193 CLR 72 at 84.

83 Typically, however, authorisation will be granted if the ACCC or the Tribunal on review are satisfied that the conduct the subject of the application, is likely to result in a net benefit to the public.

84 In circumstances where the ACCC or the Tribunal on review are not satisfied that the conduct would lead to a net public benefit, the Tribunal relevantly stated in Medicines Australia at [128] (prior to the 2017 Amendment Act):

Similarly, where the anti-competitive detriment is low to non-existent the ACCC may be entitled to say, as a matter of discretion, that it would only authorise the conduct if the public benefit to be derived from it, beyond that necessary to outweigh the anti-competitive detriment, or satisfy the per se conduct test is substantial. That is to say that the ACCC can require, in the proper exercise of its discretion, that the conduct yields some substantial measure of public benefit if it is to attract the ACCC’s official sanction. The Tribunal is in a similar position.

85 As set out above at [40], the Tribunal adopts the factual matters set out in the Agreed Factual Findings. At the time of the filing of the Agreed Factual Findings, Bendigo was not in a position to express a view on the correctness of certain of the factual matters, which were not contested by the applicants and are identified in Table 2 of the Agreed Factual Findings.

86 The Tribunal has examined the findings of fact made by the ACCC, having regard to evidence on which they were based, the submissions made by the parties about them, and the Agreed Factual Findings.

87 The following section sets out the relevant background and industry information in respect of the Australian banking industry, having particular regard to the positions of ANZ, Suncorp Bank and Bendigo.

88 Suppliers of services in the Australian banking industry are subject to significant regulatory and prudential oversight, reflecting the important role that the banking sector plays in the Australian economy. This section sets out the relevant background information in respect of that regulatory and prudential framework.

89 The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), the prudential regulator of the Australian financial services industry, prescribes strict regulatory requirements in relation to obtaining and maintaining an ADI licence. Without an ADI licence, banks are unable to offer deposit products to customers.17 This is significant because deposits can be a comparatively cheap source of funding for lending activities compared to other funding sources.18

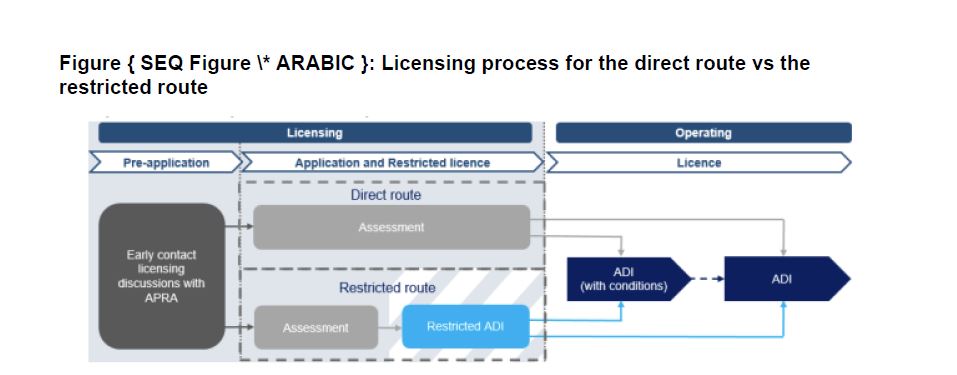

90 APRA provides two routes through which an entity can obtain an ADI licence: the “direct route” and the “restricted route”. Both routes are depicted at [4.28] of the ACCC’s Reasons for Determination, in the following figure referred to as “Figure 2”:19

91 An entity that holds an ADI licence, obtained through the direct route, can conduct the full range of banking activities, including deposit-taking, from the time it obtains the licence. To obtain a licence through the direct route, an entity is typically required to hold substantial capital resources at the point of application, or at least, a very clear avenue for access to such resources. APRA’s prudential requirements will also commence from the time the point of the licence.20

92 Alternatively, an entity that holds a restricted ADI licence, will be subject to “phased-in” regulatory obligations and in turn, only be permitted to conduct a restricted range of activities. An entity can apply for a restricted ADI licence before they are ready to be a fully licenced ADI and can do so through APRA’s Restricted ADI Licensing Framework.21

C.2.2. Calculating ongoing ADI capital requirements

93 An entity that is a fully licenced ADI must comply with all applicable prudential standards including requirements for financial resilience (such as minimum bank capital and liquidity requirements), governance, risk management, recovery and resolution, and reporting. The prudential standards establish minimum expectations for regulated entities, having regard to APRA’s purpose of ensuring that the financial interests of Australians are protected and the financial system is stable, competitive and efficient.21F22

94 APRA requires ADIs to hold a prudent minimum level of capital relative to a risk-adjusted measure of their assets, to ensure that banks are more likely to remain solvent during periods of financial adversity. Holding such a financial buffer increases the probability that ADIs have the capability to absorb unexpected losses, such as higher than usual defaults by borrowers on their loans.23

95 APRA permits two approaches for determining banks’ credit risk capital requirements: the internal ratings-based (IRB) approach and the standardised approach.24 Currently, each of the Major Banks, Macquarie and ING use the IRB approach. All other banks, including Suncorp Bank and Bendigo, use the standardised approach.25

96 Banks that are approved for the IRB approach can determine their capital requirements for credit risk using internal models that have been approved by APRA. To use the IRB approach, banks are required to hold extensive historical data, a sophisticated risk measurement framework, develop advanced internal modelling capabilities and undergo a rigorous accreditation process. Banks that use the IRB approach are also subject to more stringent regulatory requirements and more intensive ongoing supervision than banks using the standardised approach.26

97 In contrast, banks that employ the standardised approach apply risk weights, prescribed by APRA, for different types of lending. Standardised risk weights are intentionally simple and conservative. Consequently, banks that use the standardised approach may need to hold more capital against a similar exposure compared to banks that use the IRB approach.27

98 The capital framework is calibrated such that IRB capital requirements are, on average, lower than standardised capital requirements.28

99 The Tribunal notes that as capital is generally more expensive than other forms of funding, banks that use the IRB approach can typically provide lower cost offerings than banks that use the standardised approach. This gap has narrowed somewhat since (a) APRA implemented higher minimum capital requirements for IRB banks in 2017 (150 basis point increase, compared to a 50 basis point increase for standardised banks) in response to recommendations in the Financial System Inquiry Final Report in 2014 and (b) the implementation of APRA’s new capital framework on 1 January 2023.

100 The quality of banks’ capital has also improved. Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital, the highest quality form of capital that is more expensive than other sources of funding and has a directly negative effect on banks’ return on equity (ROE), accounts for most of the rise in total capital, since it was introduced as a minimum requirement in 2013.29

C.2.3. Significant financial institutions

101 The Major Banks are labelled by APRA as domestic systemically important banks (D-SIBs). This is due to factors such as their size, interconnectedness, substitutability and complexity and that their distress or failure would cause more significant dislocation in the domestic financial system and economy than less systemically important institutions. Banks designated as D-SIBs must hold more CET1 capital to meet higher loss absorbency (HLA) requirements, which increases their ability to absorb losses and, therefore, reduces the probability of failure.30

102 The designation of entities as significant financial institutions (SFIs) was recently also introduced by APRA, which includes ADIs with assets above $20 billion and those determined by APRA due to factors such as complexity of operations and group membership. This definition allows APRA to differentiate consistently between prudential requirements for larger and smaller entities.31

103 Further, in 2017, the “Major Bank Levy” of 0.015%, paid each quarter on the balance of a bank’s liabilities (funding sources), was introduced for banks with over $100 billion in total liabilities (Major Bank Levy). Currently, the Major Banks and Macquarie are subject to the Major Bank Levy, which recognises that large leveraged banks are a source of systemic risk in the financial system and the wider economy. The Major Bank Levy is also intended to level the playing field for smaller ADIs and non-ADI competitors, relative to the Major Banks, “whose size and market dominance affords them significant funding cost advantages and pricing power at the expense of their customers”.32

C.2.4. Other regulatory requirements

104 ADIs are also subject to other regulatory requirements including anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing, and conduct regulations. The government agencies responsible for setting and enforcing regulations include the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre (AUSTRAC) and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC).33 Obligations to which ADIs and financial service providers will be subject include, the requirement that to conduct a financial services business, an entity must hold an Australian Financial Services Licence and meet the conditions which attach to the holding of the licence.34 These additional regulatory obligations will impact each ADI’s compliance costs differently and relevantly, larger banks will have greater capability than smaller players to absorb fixed compliance costs.35

105 Non-bank lenders are required, in most cases, to hold an Australian Credit Licence (or operate as an authorised representative of an Australian Credit Licensee) and are regulated by ASIC. Non-bank lenders are also required to meet Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing requirements prescribed by AUSTRAC and entities that are registered financial corporations must report periodic data to APRA.36

106 There are several measures of a bank’s profitability. The most common measure is a bank’s ROE, which shows how efficiently the bank is using its equity capital to generate income.37 The Tribunal notes that net interest margin (NIM) is also a measure of a bank’s profitability, calculated by reference to its lending activities.

107 Banks generally accrue profits by lending at interest rates that are higher than the interest rates of their funding.38

108 Profitability, however, can be influenced by numerous factors, including the domestic interest rate environment, broader macroeconomic conditions, structural factors and the level of competition in each jurisdiction. The size, operating efficiency and lending profitability specific to individual banks will also impact on a bank’s ROE.39

109 To improve ROE, participants have an incentive to lower their cost-to-income (CI) ratio, which refers to the ratio of total operating costs (excluding bad and doubtful debt charges) to total income (the sum of net interest and non-interest income) and is a proxy for operational efficiency in banking.40

C.4. Price and non-price competition

110 Competition between banks can occur on price and non-price dimensions. The extent to which banks compete on both dimensions will depend on factors such as the relevant market in which they compete and the strategies that each bank employs.41

111 Price competition will occur across a range of pricing mechanisms and levers, depending on the specific product, the type of customer and what they value. For example, for loan products, which include home loans and business loans, pricing competition can occur across pricing levers such as headline interest rates, fees and charges, sign-on and cash-back bonuses and advertised and discretionary discounts.42

112 Non-price competition can occur where a business seeks to gain an advantage over competitors by differentiating the goods, services, and terms they offer to make them more attractive to buyers.43 There are also certain non-price dimensions that are particularly important to specific products and services. These include the relative speed of approval in home loans, customers’ access to and development of close relationships with specialist bankers that possess institutional and industry knowledge for agribusiness and to a lesser extent, SME banking and willingness to lend, particularly for bespoke SME business customer segments.44

C.5. Structural barriers to competition

113 Scale is important in banking because the provision of banking services involves significant fixed costs. These fixed costs include operating a branch network and maintaining head office functions, meeting regulatory compliance requirements and investing in technology to process transactions and otherwise serve customers.45

114 The Tribunal notes that in its view, as stated by [REDACTED] in an email to Mr Elliott, scale determines how these fixed costs are to be leveraged and absorbed over operational and customer bases.46 Scale is critical for banks to fund necessary investments in technology to enable them to compete effectively in the supply of banking services. The increased scale of the Major Banks compared with the regional banks enables them to spend significantly more on technology and provides them with a material competitive advantage in both price and non-price dimensions of competition.

115 Due to their larger scale, on average, the Major Banks benefit from [REDACTED].47 The Tribunal notes that, for the year ended December 2021, the Major Bank’s CI ratio was 51.9%,48 and the profit margin (net profit after tax as a proportion of total operating income) was 36.4%,49 compared with the other domestic banks’ CI ratio of 64.150 and profit margin of 25.8%.51

116 Deposits from households and businesses are the largest funding source for ADIs, accounting for approximately two-thirds of the Major Banks’ non-equity funding. Most ADIs’ deposit funding is “at-call”, meaning the depositor may withdraw funds in the short term and a substantial portion is available to be withdrawn at any time. A rising interest rate environment is generally associated with increased deposit funding costs for ADIs.52

117 ADIs also raise funds through issuing debt and securitisation in the wholesale debt market. Banks can issue short-term and long-term debt in the form of bonds and hybrid securities into the wholesale market.53

118 Smaller industry participants such as non-ADI lenders and smaller ADIs, typically source funding by using the securitisation warehouses from larger banks. As non-ADI lenders cannot raise funding from deposits, they are typically more reliant on securitisation to raise funds. Further, ADIs with a lower credit rating may have more limited access to unsecured wholesale funding markets compared with the Major Banks, and similarly may rely more on securitisation alongside their deposit funding.54

119 The Tribunal notes that deposits generally provide banks with the lowest costs of funding. A new entrant would be at a cost disadvantage if they had not first established a deposit base.

120 Further, the Major Banks and Macquarie benefit from higher credit ratings, compared with second-tier banks such as Suncorp Bank and Bendigo and other ADIs, which allows them to raise funds from wholesale debt markets at lower cost.55 Credit ratings are issued by credit rating agencies and are an important driver of a bank’s cost of and access to wholesale funding.56

121 Suncorp Bank currently receives the following long term credit ratings from the three main credit rating agencies:57

(a) S&P Global: A+ = strong chance that a borrower will meet their financial obligation, (positive outlook);

(b) Moody’s: A1 = low level of credit risk (positive outlook).

(c) Fitch: A = low risk of default, but slightly vulnerable to economic conditions on review for upgrade.

These ratings are higher than the ratings of other second-tier and regional banks because of a three-notch uplift received due to the support of SGL.58

122 The Tribunal notes that the level of switching in the Australian market for banking services will, to an extent, depend on product specific factors. In home loans, switching lenders occurs when a borrower repays their home loan with one lender (the previous lender) using the proceeds of a new home loan obtained from a different lender (the new lender), known as external refinancing.59 In retail deposits, it is common for consumers to hold multiple transaction or savings accounts across different banks, which is known as “multi-banking”. A consumer’s “main financial institution” (MFI), however, is often considered by banks to be the institution where the consumer holds their main transaction account and transacts with most frequently.60 Generally, the more price sensitive consumers are, the more likely they are to look for better deals and be motivated to switch for a better deal.61

123 The Tribunal notes the assessment by the Productivity Commission that the reasons why the banking sector has historically had a relatively low propensity for switching has been due to factors including:

(a) the costs and time involved in switching to a new provider;62

(b) varying degrees of financial literacy, levels of engagement, product complexity and information asymmetry that inhibit ready access to product information, an ability to assess the information and act on the information to make a decision to purchase or switch to a product;63

(c) cognitive and behavioural biases, causing customers to exhibit a preference for the status quo and undervalue the potential benefits of switching to a superior alternative offering.64

124 The Tribunal notes that it is important also to have regard to the distinction between “front book” pricing and “back book” pricing. Front book pricing refers to pricing of loans for new customers who benefit more from discretionary discounts, cash backs and introductory rates than existing customers who generally have higher back book pricing. The back book customers typically pay closer to the standard variable rate of interest on their home loans, which in turn is a reflection of consumer inertia and switching costs. Recently, there appears, however, to be an increased focus on back book loans. Mr Campbell, the General Manager of Home Loans in the Australian Retail Division of ANZ, gave evidence that brokers are regularly looking at their back books (customers for whom they have already arranged a loan) and where appropriate “instigate repricing activities on behalf of their customers”.65 He also gave evidence that as competition for back book customers has intensified, [REDACTED].66

C.5.5. Lack of brand recognition

125 Brand and trust are factors considered by customers when choosing who to deposit funds with.67 The Major Banks are more likely to benefit from brand recognition and have a larger share of MFI customers, who are considered valuable because they are likely to acquire more products.68

126 The nature of distribution channels dictates how customers engage with banks, and how competition takes place across the banking industry in practice.69 Banks provide products and services through a range of channels including: physical networks (such as branches, ATMs, and Bank@Post), digital channels (such as through websites and mobile apps) and intermediaries (such as brokers and relationship managers).70

127 The importance of access to branches and other physical networks as a facilitator of competition in the banking sector has declined since the expansion of online banking in the last two decades and other factors such as the increased penetration of brokers in some segments.71 Services traditionally offered by physical branches, such as opening or closing a bank account, submitting a home loan application, or customer service assistance are now increasingly offered by banks online through either web-based banking services, or through apps. A strong digital proposition is also considered increasingly important to business and SME customers. The use of digital payment methods is also increasing and notably, the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) 2022 Consumer Payments Survey found mobile payments were used by nearly two-thirds of Australians aged between 18 and 29, an increase from less than 20% in 2019.72

128 Branch access is, however, still required for certain banking transactions and activities and in person engagement is still highly valued by certain customer segments. For example, consumers who are not technologically literate, or able to use technology due to personal circumstances will continue to have a need to rely on access to branches.73

129 Nevertheless, due to the long-term decline in the importance of physical branches, financial institutions have reduced the number of bank branches and sought to develop alternative ways to deliver bank services by having several different points of presence.74 APRA data relevantly shows that the number of bank branches in Australia has reduced from 5,694 to 4,014 in the five years to June 2022.75

130 The increasingly important role for online banking as a distribution channel brings benefits to both consumers and the banks. For example, the cost of providing in-branch and call centre services can be multiples higher than for digital self-service for some customers’ banking needs.76 The benefits for consumers include faster loan application processing times, the reduced need to attend a branch for customer service assistance, reductions in search costs and an improved ability to compare products, thus facilitating switching.77

131 The increasing prominence of digital channels in the banking sector can prove challenging for banks with multiple legacy systems because undertaking digital transformation involves considerable financial investment and time. For example, ANZ has been undertaking a digital transformation program to improve its retail banking product offering and the underlying technology systems supporting these products. This includes ANZ launching an “ANZ Plus” product in March 2022, which currently includes a transaction account product and a savings account product on a mobile banking app.78

132 Further, smaller lenders, digital-only and recent entrant lenders without the requisite physical networks rely heavily on broker distribution networks and aggregator panels to gain new customers and increase scale.79

133 Brokers act as an intermediary by matching borrowers to lenders (and their loan products), assisting and advising borrowers on the loan application process and negotiating interest rates on loans.80 The Tribunal notes that brokers are under regulatory obligations to put the interests of their clients first.81

134 Aggregators, in turn, act as intermediaries between brokers and loan providers and provide the “panel” of lenders (and their associated products) that affiliated brokers choose from. Aggregators can determine which banks feature on their lending panels (typically Major Banks are strongly represented) and may provide a range of services to brokers including licensing, white-labelling services for loans, training and administrative support. Some brokers operate under an aggregator’s licence as representatives, others can only write loans from the panel lenders of the aggregator they are associated with.82 Broker distribution networks, therefore, provide lenders with access to a wider range of consumers than the direct lender channel.83

D. COMPETITION IN THE FUTURE WITHOUT THE PROPOSED ACQUISITION

135 The ACCC submits that the competition analysis in the present case requires consideration of two counterfactuals. It described the first as a No Sale counterfactual in which Suncorp Bank remains under the ownership of SGL. It described the second as a Bendigo Merger counterfactual in which there is a merger between Bendigo and Suncorp Bank.

136 The applicants submit that the only credible counterfactual is the No Sale counterfactual. They submit that the Bendigo Merger counterfactual is not a realistic possibility.

137 Both the ACCC and Bendigo contend that the Bendigo Merger counterfactual is a commercially realistic possibility in the future if the Proposed Acquisition does not proceed. They submit that (a) both Bendigo and Suncorp Bank have strong incentives to merge, (b) the merger would attract substantial scale, and efficiency benefits, (c) SGL wants to divest Suncorp Bank since it sees itself as a “pureplay” insurer, (d) a merger between Bendigo and Suncorp Bank would be value accretive to Bendigo and SGL shareholders, and (e) Bendigo has the capacity to make a compelling offer.

138 The ACCC and Bendigo submit that the likelihood of the Bendigo Merger counterfactual being a realistic commercial possibility is strengthened by the extent to which both Bendigo and SGL have invested significant resources into modelling such a merger scenario and Bendigo has actively pursued engagement with SGL in relation to a merger of Bendigo and Suncorp Bank.

139 All parties before the Tribunal accepted that, in the future without the Proposed Acquisition, the No Sale counterfactual, in which SGL retains Suncorp Bank, was commercially realistic.84

140 The ACCC, however, submits that the Tribunal should not consider the No Sale counterfactual on the basis that it is limited to a scenario, in which SGL retains Suncorp Bank, in its current form.

D.2.2. The applicants’ submissions

141 The applicants submit that while there may be a “prospect” that SGL would [REDACTED], the ACCC is wrong to suggest that the required transformational investment in home loans and SME would follow.85 The applicants submit that Dr van Horen’s evidence makes clear that [REDACTED] would only permit SGL to undertake the transformational technology investments if it is “earning the right with investors”.86

142 The applicants submit, that in any event (a) any [REDACTED] strategy is highly speculative because [REDACTED] is fraught with risk and involves several execution risks,87 (b) the evidence does not support any suggestion that [REDACTED] would confer any new found competitive strength on Suncorp Bank, (c) it is wholly speculative to presume that any [REDACTED], and (d) the interested party submission cited by the ACCC goes no further than suggesting that [REDACTED] may be a plausible counterfactual.88